Why Trauma-Informed Instruction is Vital to Success in the 21st Century Classroom

Our nation and the entire world are changing rapidly. With the rise of threats to our children’s safety like depression, lack of mental health resources, familial disruptions, and school violence and shootings, it is imperative that we equip teachers and school personnel with the tools they need to recognize and respond to all students, in all classrooms.

Our nation and the entire world are changing rapidly. With the rise of threats to our children’s safety like depression, lack of mental health resources, familial disruptions, and school violence and shootings, it is imperative that we equip teachers and school personnel with the tools they need to recognize and respond to all students, in all classrooms.

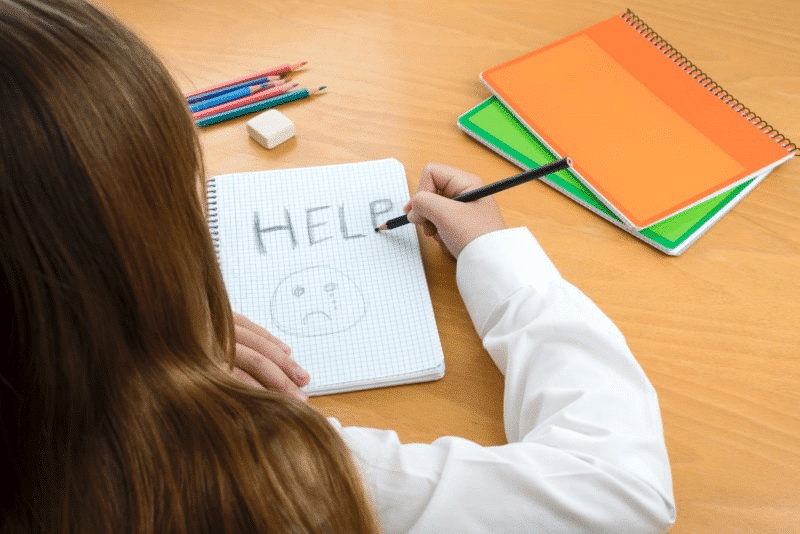

In today’s schools, students are suffering from a variety of issues; one that arises too often is mental health. Unfortunately, it is not always apparent what these students are experiencing. Depression is rampant. Emotional stress stems from a variety of external factors including depression, divorce, social media anxiety, lost friendships, bullying or simply feeling out of touch with others. It is imperative, now more than ever, that our teachers are prepared to notice when students are experiencing these types of trauma. Trauma informed practices allow teachers to be trained well beyond the obvious clues and prepares them to be aware of early, less apparent warning signs, so they can successfully and swiftly intervene to help a student in need.

Importance of trauma-informed instruction

At the University of Indianapolis, where I am the dean of the School of Education, we desire to prepare teacher candidates to be ready to teach diverse students in more technologically-advanced classrooms. We are in the early stages of centering our curriculum around trauma-based instruction and social/emotional learning. The key is understanding that we are fostering the overall relationship with students, not just teaching them. Students must view their teachers as a person who value and care for them in the classroom setting. The concept here is that students see teachers both as their instructor and someone who views them as an individual. A large part of getting students to learn is showing them you truly care for them. This helps ensure that they will in turn produce for you.

The traditional “I’m the teacher you’re the student,” climate doesn’t suit today’s classroom setting. In fact, it only deters the student, particularly one experiencing trauma. It forces them to see their instructor as another person that doesn’t care about them, and is essentially making their life harder. Think about this: our kids are in school roughly 8 hours a day, 5 days a week. That’s about 40 hours a week spent with their teachers. Isn’t it obvious that teachers play a prominent role in their students’ development? Shouldn’t those same teachers be prepared to assist and care for all of their students?

Students who are often largely ignored act out and respond in different ways to trauma, including improper classroom behavior, misconduct at home or in society, or even dangerous responses to the school itself as depicted by recent school violence and shootings in our nation. There is a clear correlation between trauma-based instruction and classroom management behavior. Students who don’t feel valued and appreciated will respond differently, sometimes negatively. That said, teachers in the 21st century classroom must be equipped with specialized training to recognize potentially problematic situations.

Our classrooms are more diverse than ever before. Today’s students have unique backgrounds—a number of them have experienced some type of trauma already, and many more unfortunately will be traumatized in their own classroom or school environments. That begs another question: how do we, as educators, properly care for and lead every student regardless of background? Something that is often overlooked is the fact that the teaching profession is predominantly white and female. Our teachers coming from this demographic need to be more culturally sensitive to the diversity in their classrooms, while we continue to drive more diverse teachers into the profession. Educators across the nation are working to inject more diversity into school systems, but as long as the climate remains as it is, we must instruct current educators on how to approach diversity in the classroom. Students from different backgrounds may come to teachers with problems that they have not experienced in their own lives or culture. This only strengthens the case to prepare all teachers to be trained in social/emotional instruction and cultural awareness.

What does it take to implement such changes?

Conversation—talking with our faculty and listening to our School of Education students, who tell us, “I don’t know how to handle this type of student,” is key. In our program, these aspiring teachers have the unique opportunity to go into the classroom in their first year—which allows them to see eye-opening realities. We hear our teacher candidates say that they are not comfortable teaching in diverse settings. That can be attributed to a lack of experience or cultural awareness to engage with students who don’t look like them. They are overwhelmed when encountering young people who have not eaten a meal that day, have not seen their parents in days or longer, or students with poor hygiene. There is also a secondary trauma piece at play here. When our candidates go into classrooms and see this, they become depressed and hurt. When children are in trauma, it effects their learning and their teachers. Right now, we are working with our teacher candidates to take a step forward. We are going back to our curriculum to review and revamp it to be more sensitive to the evolving climate of education. This curriculum will offer more seminars and courses on cultural awareness and the understanding of different populations. It starts with our faculty. They must be engaged and willing to infuse the curricula with trauma-based instruction and social/emotional learning. With this, our teacher candidates can recognize even the most subtle warning signs in order to help their students deal with not only the challenges of learning, but trauma as well.

Everything comes with challenges

This is a major shift. The school districts are saying they need teachers who can be more connected to the students and recognize signs of trauma and emotional stresses. Some of this can be handled inside the classroom as opposed to sending students in trauma to a social worker. Teachers need to develop skill sets before leaving their respective teacher prep programs. Where does trauma-based instruction fit in our competitive programs? The challenge lies in getting faculty to embrace teaching students these types of objectives and learning outcomes. We are working through that as a faculty and finding a place for this in our degree plans. It is imperative that we respond to the needs of our school districts and send them better-prepared teachers to recognize and address trauma. But that requires a change in the mindset of our faculty.

We are still in the infancy stage of moving forward with this initiative. The number one goal is that our students be educated in such a way that as teachers they are able to recognize and respond to students in trauma. Our teachers will not only deliver subject matter instruction, but will also care for the whole child. It takes an entire school community to foster success for our students, teachers, school leaders, communities, and society at large.

John A. Kuykendall is the dean of the University of Indianapolis College of Education.